Pay for performance (P4P) is the latest rage in healthcare quality monitoring. Paying physicians more who provide high quality care makes sense intituitvely. The U.S. isn’t the only country to hop on the P4P bandwagon.

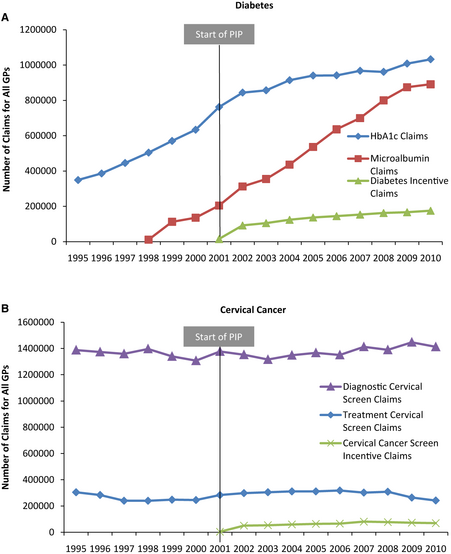

In 2001, the Australian government initiated a financial incentive program for “improved management of diseases such as asthma and diabetes and increased screening for cervical cancer” for GPs, who are paid for each patient visit on a fee-for-service basis. The voluntary program, called the Practice Incentives Program or PIP, is open to GPs in practices that are accredited or undergoing accreditation and it continues today. Participation is incentivized with one-time, sign-on payments to medical practices, which are approximately $250 per full-time GP in the practice for the asthma and cervical cancer programs and $1,000 per GP for the diabetes program.

The diabetes and asthma incentives are based upon GPs providing patients with a cycle of care over a 12-month period. For diabetes, the cycle includes providing patients recommended tests (HbA1c, microalbuminuria, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and blood pressure); relevant examinations (feet and eyes); reviewing medications, diet, physical activity, and smoking status; measuring body mass index; and providing diabetes self-care and related education. A GP earns A$40 for each patient who completes the cycle of care, in addition to the regular consultation fee. To earn P4P incentive payments, the GP has to bill specific PIP-related codes for the visit. There is also a practice-level outcome incentive for practices that complete cycles of care for 20 percent or more of their patients with diabetes in a year (A$20 per diabetes patient). For asthma, the incentive is A$100 for each patient who completes the cycle of care.

However, the question is, does it work? A paper by Greene (2013) examines just this question. At first glance, the trend seems to be yes.

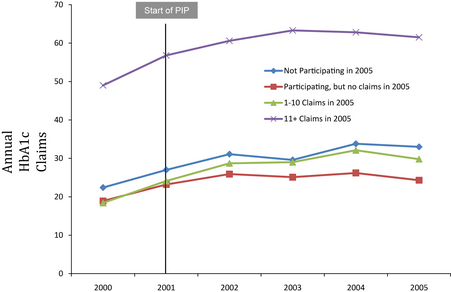

However, it appears that P4P may not affect physician behavior directly. As the chart below shows, although overall diabetes and asthma screening increased, the rise did not differ between physicians who participated in the program and those who did not. A fixed effects regression confirms these findings.

Why didn’t P4P make a big difference? The author followed up with a number of physician interviews. Responses included:

- “It’s money for doing what you were already doing.”

- “From a clinical point of view, yes [the care cycles are] a priority and we do it.”

- “I’m not improving their care, I’m just doing paperwork. And for that minimal return, it’s just not worth it”

- “In the time I could muck around working out whether I’ve done it this year, have I done all the bits and pieces, ticked all the boxes, rather than do that, I’ll just see someone else.”

Souce:

- Greene, J. (2013), An Examination of Pay-for-Performance in General Practice in Australia. Health Services Research. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12033

1 Comment