This is the question a paper by Chambers et al. (2019) aims to answer. The authors analyzed coverage decision of 204 drugs (or 409 unique drug–indication pairs based on information from the Tufts Medical Center Specialty Drug Evidence and Coverage (SPEC) database. This database contains coverage information for 17 or the top 20 health plans in the U.S. They authors use this database to evaluate whether the payers imposed restrictions such as:

- Patient subgroup restriction: Requiring patients to meet certain clinical criteria (e.g., disease severity

- Step therapy: Requiring patients to first try and then fail an alternative–typically cheaper–treatment before gaining access to a drug of interest

- Prescriber restriction: Requiring that only certain physician specialties (e.g., oncologist, rheumatologist) prescribe the drug,

- Combination therapy: Requiring that a drug to be used concomitantly with another medication

- Other.

Using this approach, the authors find that:

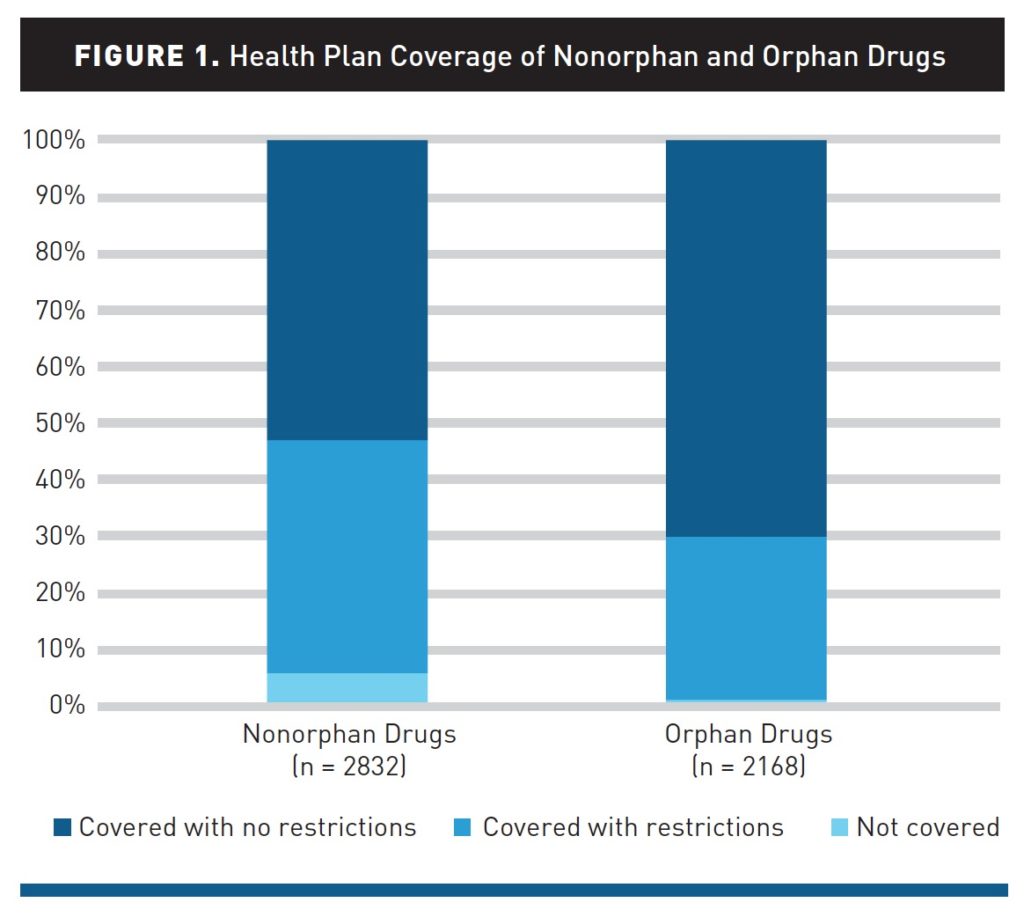

Health plans are less likely to restrict orphan drugs compared with nonorphan drugs. Of orphan drug decisions (n = 2168), plans did not apply coverage restrictions in 70% of cases, applied restrictions in 29%, and did not cover in 1%. In contrast, of nonorphan drug decisions (n = 2832), plans did not apply coverage restrictions in 53% of cases, applied restrictions in 41%, and did not cover in 6%. The frequency of restrictions for orphan drugs varied from 11% to 65% across plans. The attributes of orphan drugs that were more likely to be associated with restrictions than others included drugs for noncancer diseases, drugs with alternatives, self-administered drugs, drugs indicated for diseases with a higher prevalence, and drugs with higher annual costs (all P <.05).

These average do hide some variability. The most generous plan covered all orphan drugs with only 11% having any restrictions, whereas for 2 of the 17 plans considered in the study, 50% or more of orphan drugs had some restrictions on access.