In many countries including the US and England, hospitals are paid by payers (i.e., commercial insurers and governments) on a per-admission basis with more reimbursement for treating patients with more severe conditions and lower reimbursement for treating patients with less severe conditions. This system is known in the U.S. as the diagnosis-related group (DRG) system, since DRGs are used to assess admission severity and also hospital reimbursement levels. In England, the change in the system was implemented as described in Aragón et al. (2022):

From 1989 the intention was for purchasers to enter into contractual agreements with hospitals with discretion as to exactly what form those agreements took. However, the system of setting hospital level budgets – known in the purchasing terminology of the NHS as a Block Contract – tended to persist in spite of the intention that purchasing should move toward activity-related payments. Hence, starting in 2003 the DRG system we are studying began to be rolled out. In the NHS this was called [Payment by Results] PBR which is functionally a DRG system. Patients treated by a hospital are assigned to a category called a HRG which is equivalent both in purpose and definition to a DRG. The hospital is paid a fixed, nationally set, price for each patient in each HRG. Pertinent to our study the system differentiates between patients whose hospital treatment is planned in advance – termed elective treatments – and those who are admitted as an emergency (either through an emergency department or referred as an urgent case by their physician)

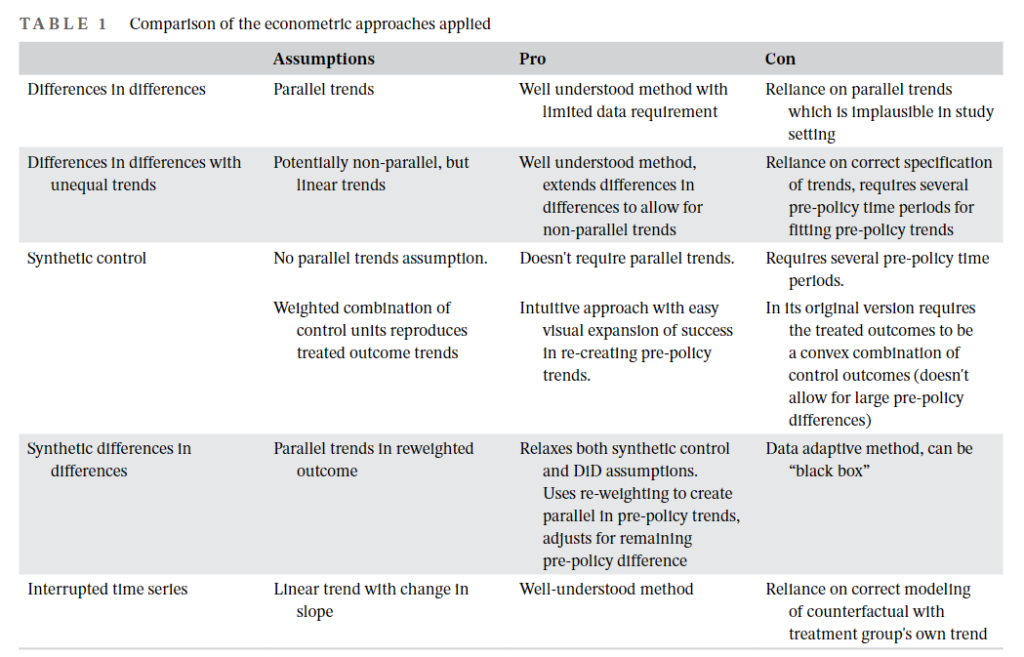

To examine the impact of implementing the DRG system on hospital length of stay (LOS), the authors use data from the Admitted Patient data set of Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) in England and for their comparison group the authors used equivalent data from Scotland called the Scottish Morbidity Record 01. With these data the authors use a variety of econometric specifications including difference-in-differences (DiD), synthetic control (SC) and interrupted time series (ITS). As they found the SC approach failed to find a good fit in the pre-policy period, the authors apply a synthetic differences in differences developed by Arkhangelsky et al., 2019; this approach can adjust for the bias resulting from poor pre-policy fit. The pros and cons of each econometric approach are listed in the table below:

Using this approach, the authors find that:

For elective care we estimate a long run effect (measured in 2013) of between −1.4 and −0.7 days using DiD and ITS methods. The SDID gives an estimate of −0.4. These figures correspond between 35% and 70% reductions relative to the 2002 average LOS. For emergency care the full range of results is from −1.4 to −3 days, corresponding to between 14% and 30% reductions relative to 2002 average LOS. In comparison the initial effects over the period 2003–2005 are smaller and of borderline significance. The results for emergency treatment in particular are not well-determined over this earlier period.

While it is not surprising that LOS decreases after implementing a DRG system, it is interesting that it takes some for hospitals to fully implement this shorter LOS. Potentially, changing management practices took time to roll down to staff in terms of how to discharge patients more quickly while minimizing any impact on patient quality of care.