That is the question answered in a paper by Autor et al. (2022). Some background on PPP:

Congress enacted the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), which provided uncollateralized, low-interest loans of up to $10 million to firms with fewer than 500 employees—loans that were forgivable on the condition that recipient firms maintained employment and wages at close to pre-crisis levels in the two to six months following loan receipt.

PPP was one for three large federal initiatives to combat the impact of COVID-19 on the US economy. These three (and relevant funding) include:

- Paycheck Protection Program: $800 billion

- Stimulus checks: $800 billion

- Unemployment benefits: $680 billion

Note that each of these 3 programs was approximately the same size as the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA), the main fiscal stimulus passed in response to the 2007-2009 Great Recession.

What was the impact of PPP? The authors found that it:

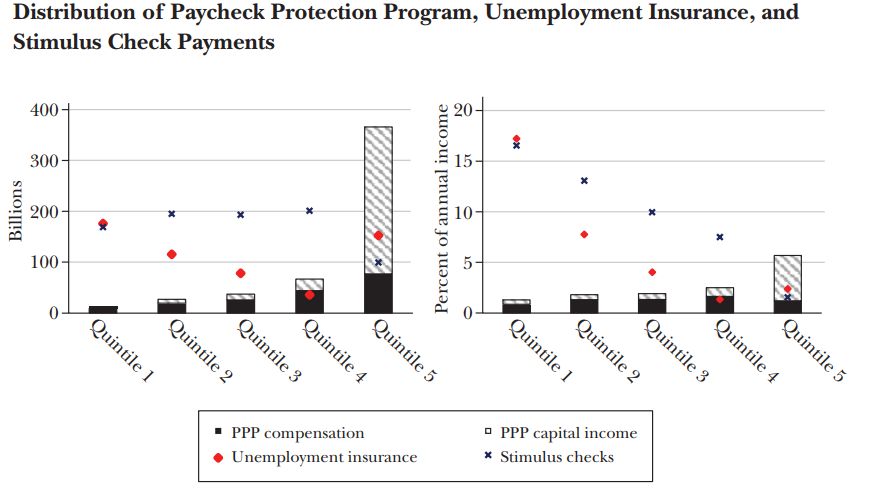

meaningfully blunted pandemic job losses, preserving somewhere between 1.98 and 3.0 million job-years of employment during and after the pandemic at a substantial cost of $169,000 to $258,000 per job-year saved. PPP also reduced the rate of temporary closures among small firms, though it is less clear whether it reduced permanent closures. The majority of PPP loan dollars issued in 2020—66 to 77 percent— did not go to paychecks, however, but instead accrued to business owners and shareholders. And because business ownership and share-holding are concentrated among high-income households, the incidence of the program across the household income distribution was highly regressive… three-quarters of PPP benefits accrued to the top quintile of household income. By comparison, the incidence of federal pandemic unemployment insurance and household stimulus payments was far more equally distributed.

Note that this lack of targeting does not necessarily make PPP a bad program. Policymakers could have insisted on better targeting and provided stricter thresholds for getting the money. Doing so, however, likely would have substantially slowed down aid delivery and reduced program efficacy.

Some additional information:

- Disbursement was rapid: $505 billion in first draw loans were issued and all but 7% were issued in 2020, most in April and May.

- Business owners, not employees are primary beneficiaries. For the first 2 tranches of support 23%-34% of loans went to worker compensation; 66%-77% of loans went to business owners or creditors.

- A regressive stimulus. Compared to unemployment insurance or the stimulus package, PPP was regressive in nature (see figure below).

Some may argue that PPP’s regressive nature is highly problematic. All else equal, redistribution should favor the poor. However, if small and medium sized businesses were to go bankrupt, that would be detrimental to the economy not only in the short-run. If businesses dissolve, the know-how these businesses built up could disappear, as it is not easy to reconstitute a business once it has folded. Further, prices could rise due to a lack of competition if many small and medium sized businesses–perhaps with a less secure balance sheet–went under.

Program description

Businesses were permitted to draw PPP loans worth up to ten weeks of payroll costs—including wage and salary compensation not to exceed $100,000 per worker, as well as paid leave, health insurance costs, other benefit costs, and state and local taxes—with a maximum loan size of $10 million dollars.

While the moniker Paycheck Protection Program suggests that the program was focused solely on employment, the criteria for loan forgiveness reveal another complementary goal: providing firms with liquidity to meet non-compensation obligations to creditors (like suppliers, banks, and landlords). Businesses had to do four things to qualify for PPP loan forgiveness: 1) spend at least 60 percent of the loan amount on payroll expenses; 2) spend (at least) the full loan amount on total qualifying expenses, including payroll, utilities, rent, and mortgage payments; 3) maintain average full-time equivalent employment at its pre-crisis level; and 4) maintain employee wages at no lower than 75 percent of their pre- crisis level.