Why do physician practice patterns differ so much? One cause of the regional variation the utilization of medical care is due to regional variation in patient health status. Maynard, however, states that variation in patient health is not a primary cause of regional variation in the utilization of medical services. He cites an article by Bloor et al (1977) that examines high and low-rate surgeons in Scotland.

They found that low rate surgeons chose watchful waiting more often and tended to base their decisions on clinical history rather than immediate physical examination, the practice of high rate surgeons. They concluded that …practice variation ‘can be attributed to differences amongst specialists in their assessment practices: local difference in nature of specialist practice “create” local difference in surgical incidence ’; that is, a primary cause of clinical variation was the differences in medical opinion and not the differences in morbidity.

On way to standardize the supply of medical services is to use pay-for-performance (P4P) programs to incentivize best practices. Maynard (2012) reviews P4P initatives such as the UK’s Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) and the US Premier Hospital Quality Incentive Demonstration (HQID). He also outlines research questions to consider when designing new P4P programs. A discussion of each is below.

- Who’s Performance? Consumers, individual providers, organizations (e.g. wards or general practices) or institutions (e.g. hospitals). “There is some evidence that the best focus of incentives is the clinical team. For instance, the NHS incentive scheme for general practitioners in primary care was conditional on practice or team performance and improved activity performance. A counter-argument is that P4P incentive schemes should be focused on the institution rather than the individual physician as that is where the financial risk lies”

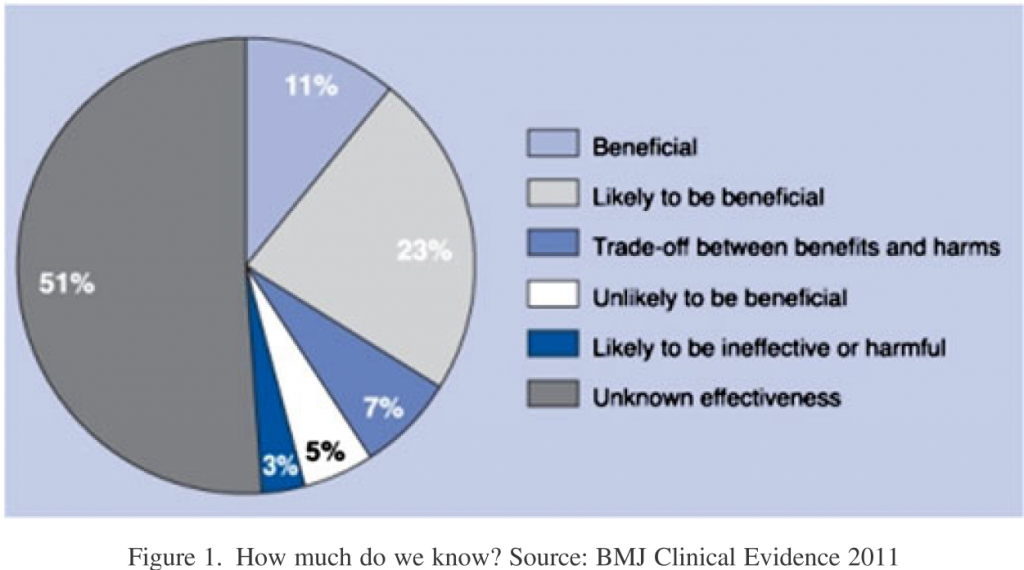

- What performance? Although outcome measures are preferred, measuring outcomes is often difficult. To control for patient comorbidities, complex risk adjustment models are often required. Thus, many P4P programs turn to process measures, which identify whether providers completed a specific task. Unfortunately, much of medical care does not have an established best practice (see below).

- Financial or non-financial incentives? Maynard correctly writes that “The effects of financial (bonuses and penalties) and non-financial incentives (reputation and peer pressure) are difficult to separate. Does public reporting increase quality or are financial incentives (beyond the corresponding rise in income from indirect reputational effects) needed to improve quality?

- Penalties or Bonuses. Maynard cites Kahneman and Tversky and argues that penalties may be more effective than bonuses due to loss aversion. This may be true in the short-run, but if P4P financial incentives are in place over time, the previous reference place will lose meaning and P4P will be seen as a gradient. Maynard does make a good point that it is often difficult to get provider buy-in to P4P if only penalties are offered.

- Size of the incentives. There is little evidence of the magnitude of incentivizes needed to affect behavior. One reason is that—in the US at least—providers receive reimbursement from multiple payers and, thus, even a large bonus may make up a small share of the provider’s overall income.

- Duration of effect. “Targeting particular processes and outcomes elicits change. But is that effect permanent and after how long can bonuses be shifted to other aspects of care without any decline in the initially targeted activities”

- Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Maynard wisely mentions the concept of opportunity costs. Specifically, what health and process gains, if any are given up in the nonincentivised areas of hospital activity? This issue was first articulated by Holmstrom and Milgrom.

Source:

- Maynard, A. (2012), The powers and pitfalls of payment for performance. Health Econ., 21: 3–12. doi: 10.1002/hec.1810