How do people respond to financial incentives? In the medical world, physicians often are paid fee-for-service (FFS) or capitation. Physicians receiving FFS reimbursement receive additional compensation for each additional service they do. For instance, physicians under FFS receive twice as much compensation for 2 office visits as they would for 1 office visit. On the other hand, physicians receiving capitation receiving a flat rate per member per month to care for their patients. Thus, these physicians receive the same compensation for each patient regardless of whether the patient would use 2 or 1 office visits (or any other service for that matter). In summary, FFS physicians have an incentive to perform more services whereas capitation physicians have an incentive to do less.

Do people respond to these incentives in the real world? A paper by Brosig-Koch, Hennig-Schmidt, Kairies-Schwarz, and Daniel Wiesen (2015) find that the answer is yes.

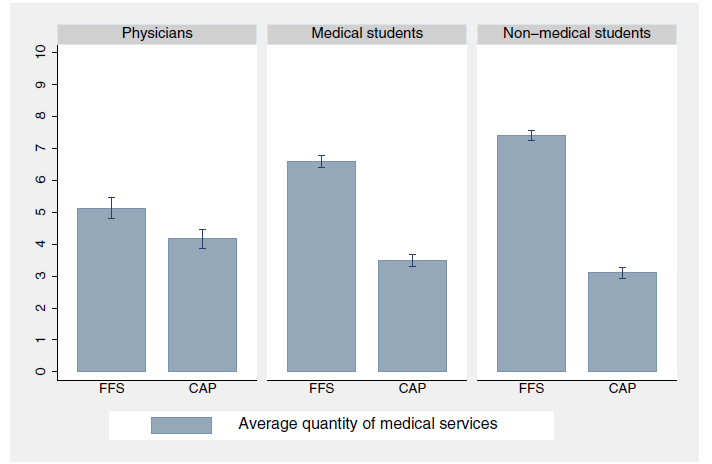

Physicians, medical students, and non-medical students respond to incentives inherent in the payment systems in a consistent way: More medical services are provided in fee-for-service compared to capitation. This finding is in line with the theoretical health economics literature (e.g., Ellis and McGuire, 1986) and corresponds to results from earlier empiricaland experimental studies (e.g., Gaynor and Pauly, 1990; Hennig-Schmidt et al., 2011). The degree to which subjects respond to incentives varies by subject pool: Physicians’ behavior is less affected compared to medical and non-medical students.Moreover, our findings are robust regarding subjects’ gender, age, and personality traits.

The most interesting finding is not that FFS reimbursement increases the amount of services respondents provide, but rather than physicians are the least likely to respond to incentives compared to medical students or non-medical students. There are a number of potential explanations for this. Perhaps, physicians care more about their reputations than the students and thus have an incentive to increase services provided under capitation. Alternatively, physicians may have internalized professional norms more than medical or non-medical students.

Note that other factors clearly influence service provision and patient severity of illness did increase the among of services provided.

Source:

- Jeannette Brosig-Koch, Heike Hennig-Schmidt, Nadja Kairies-Schwarz, Daniel Wiesen, Using artefactual field and lab experiments to investigate how fee-for-service and capitation affect medical service provision, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, Available online 30 April 2015, ISSN 0167-2681, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2015.04.011.

I am an economics student and I have been following the careers of some of the most influential entrepreneurs in the United States in order to help guide me on my career path. Joel Hyatt is one of the most successful lawyers in the United States. I have learned a lot by following his career. Here is a comprehensive blog post that gives some background information about Mr. Hyatt. https://disruptivelegal.wordpress.com/2014/01/21/who-is-joel-hyatt-the-little-known-pioneer-of-innovation-in-the-legal-services-industry/