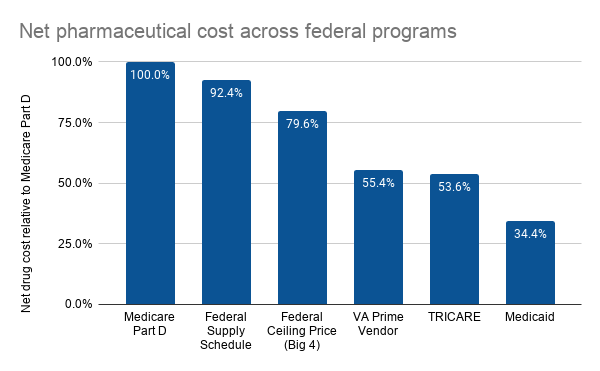

A number of different federal agencies buy prescription drugs. However, the price at which these pharmaceuticals are purchased varies dramatically. To quantify this variation, a 2021 report from the Congressional Budget Office examines the following prices:

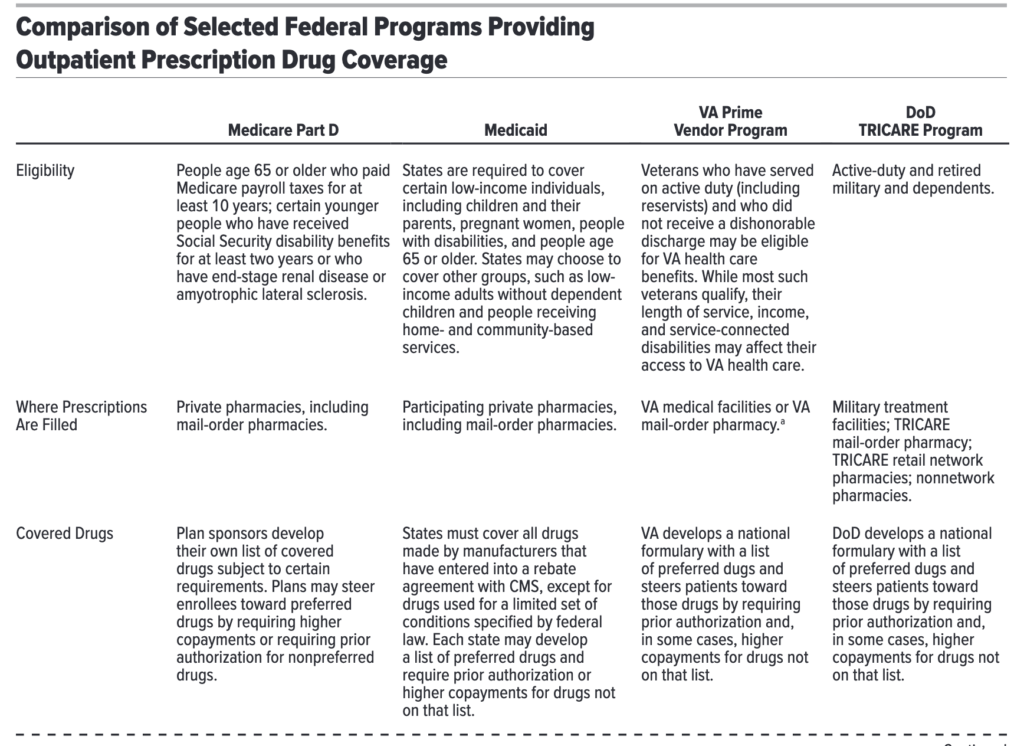

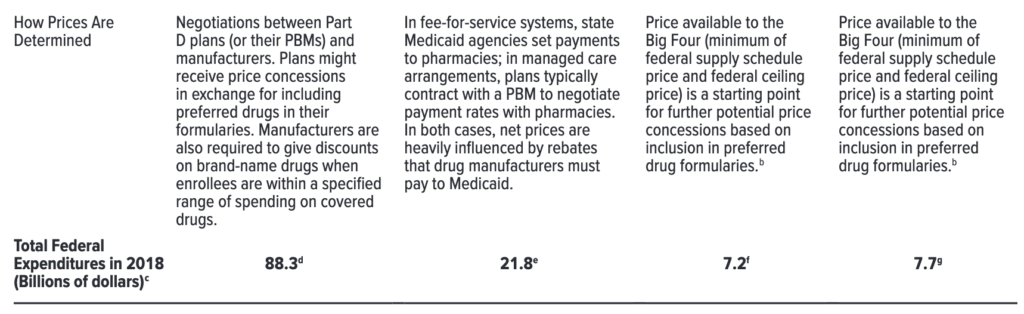

- Medicare Part D: the prescription drug program for Medicare beneficiaries. Prices are set when private insurers (or pharmacy benefit managers [PBMs] operating on their behalf ) and pharmaceutical manufacturers negotiate to determine drug prices under market conditions similar to those facing commercial insurers.

- Medicaid: The health insurance program for the disadvantaged. Net prices are determined largely by manufacturer rebates that are specified by federal statute reduce drug prices

- The Federal Supply Schedule (FSS). This program establishes prices available to all direct federal purchasers (i.e., federal agencies that buy drugs directly from wholesalers or manufacturers and provide their own dispensing services). Prices are determined through a combination of statutory rules and negotiation.

- The federal ceiling price (FCP) program. This program establishes prices available to the Big Four agencies, which include the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Department of Defense (DoD), the Public Health Service, and the Coast Guard. These four agencies generally pay lower prices than other direct federal purchasers because of a statutory cap on the prices they pay.

- VA’s prime vendor program and TRICARE. This DoD program consists of both the agency’s prime vendor program, in which drugs are dispensed at military treatment facilities (MTFs) or by mail, and the TRICARE retail pharmacy network. These prices are typically lower than the prices paid by the Big Four agencies under FCP, because the VA and DoD: (i) use national formularies of preferred drugs, (ii) the formularies steer patients to lower-cost drugs, and (iii) buy drugs in large volumes.

CBO examined a basket of pharmaceuticals consisting of the 176 top-selling drugs and a sample of 64 high-priced drugs. This analysis examined only outpatient pharmaceuticals and excluded physician-administered drugs. Prices were calculated as average net price (i.e., prices after rebates) per standardized prescription, where a standardized prescription corresponds to a 30-day supply of medication. Using this approach, CBO found significant variation in net drug cost across federal programs.

Note that although CBO did include pharmaceutical dispensing fees in their analysis for Medicare Part D, Medicaid, and TRICARE, dispensing fees are not included for VA and DoD–although CBO noted that adjusting for this difference would have a modest impact on the results.

So is the solution to just set all prices to Medicaid best price (for those who want lower prices) or set prices to Medicare Part D prices (for those who want to better incentivize innovation)? CBO things the answer to the question is more difficult to answer.

The comparisons of average drug prices among federal programs in this report do not indicate how prices would change if one program’s method of determining prices was extended to other programs. In such a scenario, drug manufacturers would very likely alter their price negotiations in ways that could affect prices in all federal programs and in the private sector… An analysis by CBO found that the introduction of the Medicaid drug rebate program in 1991 increased the net prices paid by some private payers.

This is likely espeically true since Medicare Part D is the largest federal purchaser. In 2017, Part D spending was $88.3 billion, Medicaid was $21.8 billion, DoD $7.7 billion and VA $7.2 billion.

More details on the CBO report are below.

One can see a nice overview of the different federal drug purchasers from the table below.

While one may think that Medicare Part D plans have a large incentive to reduce cost, that may not entirely be the case. The reason is that the federal government–rather than the PDPs themselves–are bearing an increasing amount of the drug costs due to the reinsurance provision.

From 2007 to 2017, the share of basic benefit costs for which plans were responsible fell from 53 per-cent to 29 percent among enrollees without Part D’s low-income subsidy and from 30 percent to 19 percent for enrollees receiving that subsidy…The reinsurance provision of the Part D program has contributed to those changes. (Under the reinsurance provision, the Medicare program pays nearly all of the drug costs for a beneficiary after the total drug spending for that person exceeds a specified threshold.)

Medicaid rebates

By statute, Medicaid rebates have two components. Note that Medicaid managed care can negotiate additional rebates.

…the basic rebate, is the larger of either a flat rebate amount—currently 23.1 percent of the average manufacturer price (AMP) of a brand-name drug—or the difference between the AMP and the “best price” (the lowest net price extended to any private buyer, excluding Part D plans)…The second part of the Medicaid rebate is based on the rate of increase in the AMP. If the AMP grows faster than overall inflation as measured by the consumer price index for all urban consumers (CPI-U), the excess amount of that growth is owed as an additional rebate…In addition to the basic and inflation-based rebates, states and Medicaid managed care plans may negotiate for supplemental rebates beyond those statutory rebates by using preferred drug lists