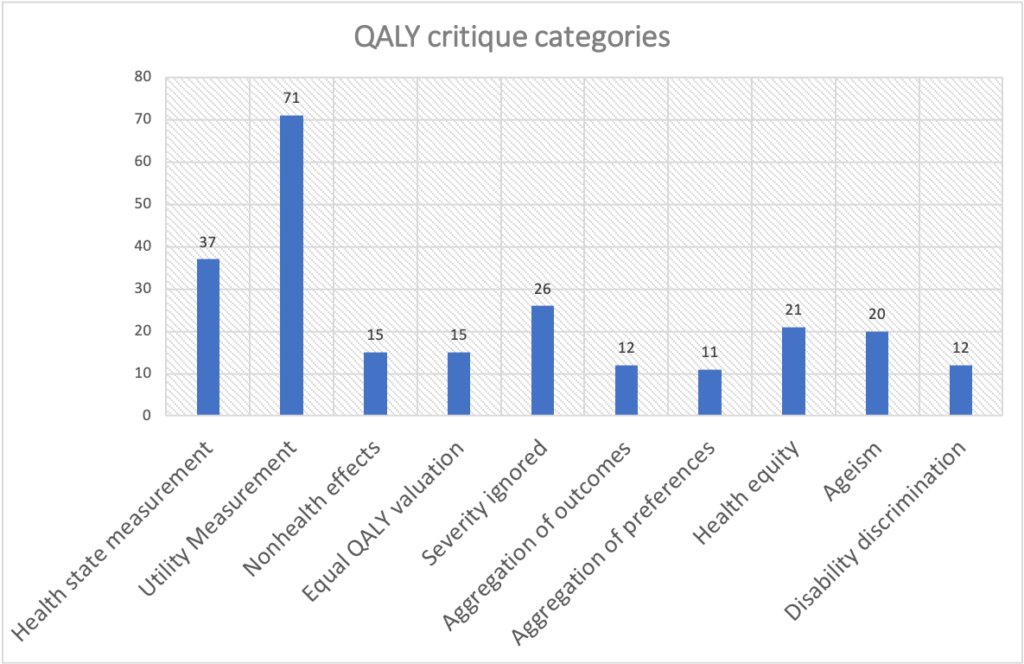

A paper by Rand and Kesselheim (2021) in Health Affairs this month conducts a systematic literature review to answer this question. Based on 113 articles they identified in peer-reviewed journals, they identify the following 10 criticisms categories.

The graph above has each criticism category and the number of peer-reviewed articles that mention this critique type. Each of these criticism categories are subdivided into specific critiques:

| Criticism category | Specific criticism |

| Health state measurement | Validity of tools to measure health state; Reliability among tools; Difficulty of self-reporting for some groups; (e.g., children, dementia); Insensitivity to specific conditions or changes in health; Prescriptive definition of health-related quality of life (excludes some health domains and well-being beyond health); |

| Utility Measurement | Validity of utility measurement; Reliability between utility measures: different methods produce different results; Elicited utilities are changed by the perspective the question or responder takes, including whether ill health happens now or later & risk-aversion; Utility scores elicited from the public are different from those of patients who experience the health state; Utility values may change over the life course or not be fixed; Individual preferences are not compatible with the utility theory of QALYs: People do not hold time and quality of life in a constant proportional, linear trade-off; Measures utilities per health state rather than utility of moving between health states; Death should not be treated as a quality-of-life utility; it is a time measurement Unclear how to value certain conditions or outcomes, such as stillbirth |

| Nonhealth effects | Social utility and externalities are not measured; Effects on dependents and benefits to others not measured; Scientific spillover (future innovation or learning) not measured |

| Equal value of QALY regardlesss of recepients | Neutrality overall: equal value to the QALY irrespective of other characteristics of the recipients; QALYs ignore distribution of health |

| Severity ignored | Severity of the condition is not accounted for in QALYs (that is, starting health state not reflected in QALY gain); QALYs ignore endpoint health state (whether treatment results in a poor health state or whether a better state would have been possible); QALY gains reflect capacity to benefit and magnitude rather than need or past ill health; |

| Aggregation of outcomes | QALYs in total counted, not individual lives; assumes that gains can compensate for losses; Does not draw a distinction between saving or extending lives and improving quality of life; Ignores whether a health state was improved or decline prevented; |

| Aggregation of individual preferences | Individuals’ values & preferences are different, but they are assumed to value QALYs equally; Utilities should not be interpersonally compared and aggregated; Individuals’ preferences should not apply to others; Effects for individuals may be different from the average (outliers); |

| Health equity | QALYs are insensitive to health distribution, do not account for equity or fairness; QALY neutrality does not reflect public preferences about health equity |

| Ageism | Bias by age because remaining life expectancy means younger populations can produce more QALYs; QALYs should weight health gains for younger populations to achieve equity in life expectancy; |

| Disability/chronic condition discrimination | A disability or chronic condition reduces quality of life and therefore potential to gain QALYs; People with disabilities are often unwilling to trade off time for quality of life, leading to high utility scores for their health state; |

To find out more about each of these criticisms, do read the whole paper here.