Medicare Part D has had a very odd benefit structure. First, you have a deductible with no coverage; then you get some coverage, then there is a coverage gap or “donut hole” with no coverage and finally there is very generous coverage in the ‘catastrophic phase’. This structure was espeically problematic for patients with high drug costs because they had very high out of pocket costs during the coverage gap phase. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), however, gradually eliminate the Medicare prescription drug coverage gap between 2011 and 2020 (and in fact the Inflation Reduction Act will eliminate the coverage gap entirely). A key question is, how did the ACA’s closing of the coverage gap impact patient out-of-pocket (OOP) cost and supply of branded vs. generic drugs.

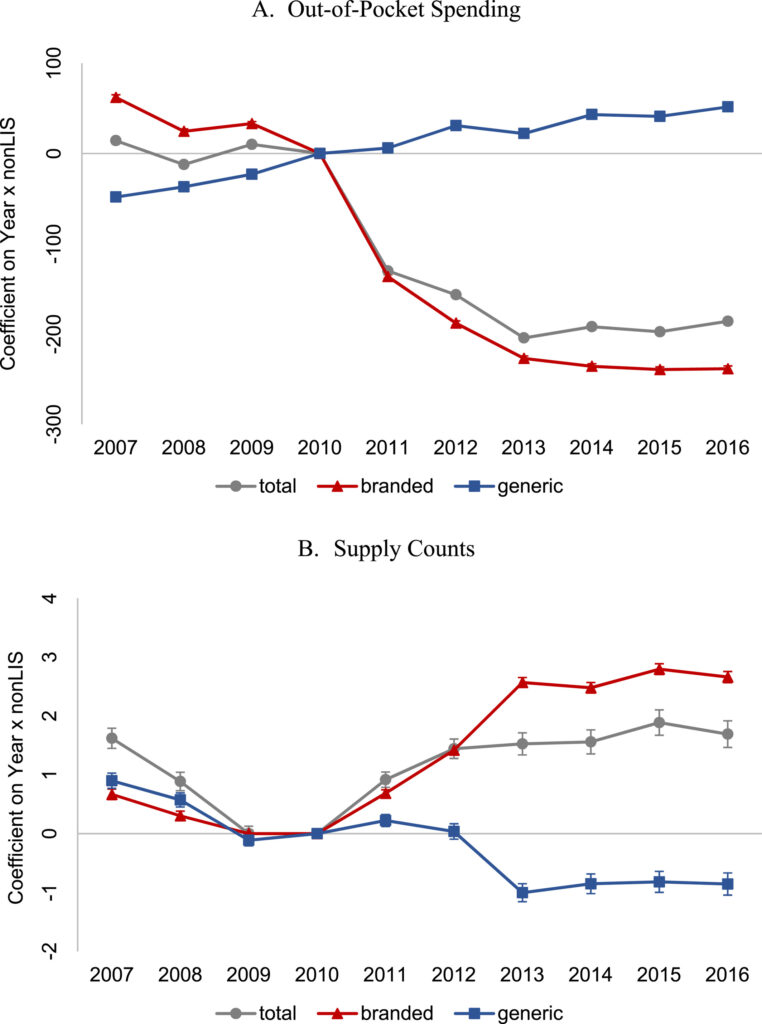

A study by Liu et al. (2022) aims to answer this question. They use Medicare Part D claims data between 2011-2020 in the analysis. A difference in difference approach is used where changes in OOP cost and branded/generic supply were evaluated before and after the ACA intervention. The ‘intervention’ group was individuals who did not qualify for low-income subsidy (i.e., non-LIS) (as these individuals benefit from the closing of the coverage gap); the control group is made up of LIS beneficiaries as these individuals already have limited or no cost sharing for drugs, so the ACA provision would have no impact on their out of pocket cost. Using this approach, the authors found that:

… filling the coverage gap significantly decreased patients’ OOP spending, mainly due to a substantial reduction in OOP spending on branded drugs. We provide evidence that the coverage gap closure contributed to a larger reduction in OOP spending and increased use of branded drugs for beneficiaries who fell in the coverage gap or had more chronic conditions. This was in line with the intent of the ACA coverage gap provisions, which was to reduce the financial burden associated with prescription drugs. We also find that the policy increased utilization of branded drugs due to the large discounts on branded drugs during the coverage gap phase in the initial years of the policy

You can read the full paper here.